100-YEAR-OLD BRAIN MYSTERY: WHAT DOES THE TEMPORAL POLE DO?Featuring: Marsel Mesulam, MD

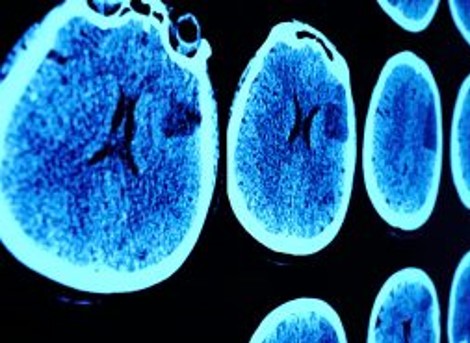

A colorful, vital function of this human brain region revealed Every part of the brain surface (the cerebral cortex) has a specific job description. Some areas move the arms, others the legs, still others make it possible to see or speak. But one part of the brain surface, a region called the temporal pole because it is at the very tip of the temporal lobe, could not be linked to a specific function for at least the first 100 years of research on the cortex, according to a recent study published in Annals of Neurology. Northwestern Medicine scientists have just discovered that this mysterious and seemingly silent surface is actually one of the most colorful regions of the brain. It has critical functions in word comprehension, face recognition and the regulation of behavior. The scientists were able to identify this region’s previously unknown function through the investigation of 28 patients with a unique disease, known as TDP-C, that ultimately destroys the temporal pole. The cases reviewed post-mortem offer the most precise delineation of the brain areas that are first hit in a disease that progresses over 10 to 15 years. “Research on this disease helps us understand how the brain decodes the meaning of words, the feelings of others and the identity of faces,” said study corresponding author Marsel Mesulam, MD, chief of Behavioral Neurology in the Ken and Ruth Davee Department of Neurology and a Northwestern Medicine neurologist. “This knowledge will help to determine the nature of the disease and the nature of brain networks that are responsible for word comprehension, person identification and the monitoring of interpersonal conduct.” Now Northwestern investigators are studying the relationship between the temporal pole and these complex functions, and the nature of the relationships between TDP-C and the temporal pole. “Answering these questions is key for helping patients with this condition,” said Mesulam, also the Ruth Dunbar Davee Professor of Neuroscience and founder of the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease. “The next steps in the research are to identify the unique properties of the areas targeted by TDP-C, determine how the disease progresses and find out if there are patient-specific risk factors.” The patients with TDP-C had been followed longitudinally at the Mesulam Center. The longitudinal data on brain function was linked to the tissue damage seen by examination with the microscope after autopsy. Other Northwestern authors include Emily Rogalski, PhD, the Ann Adelmann Perkins and John S. Perkins Professor of Alzheimer’s Disease Prevention in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences; Tamar Gefen, PhD, assistant professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences; Margaret Flanagan, MD; Rudolph Castellani, MD, professor of Pathology; Pouya Jamshidi, MD; Elena Barbieri, PhD; Jaiashre Sridhar, MS; Allegra Kawles; Sandra Weintraub, PhD, professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences; and Changiz Geula, PhD, research professor in the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease. This article was originally published in the Feinberg School of Medicine News Center on July 13, 2023. |

Marsel Mesulam, MD, chief of Behavioral Neurology in the Ken and Ruth Davee Department of Neurology and a Northwestern Medicine neurologist.

Refer a PatientNorthwestern Medicine welcomes the opportunity to collaborate with you on the care of your patients.

|

Northwestern Medicine Breakthroughs for Physicians

|

About Us Terms of Use Privacy Policy How to Vote for U.S. News & World Report Best Hospitals

© 2024 Northwestern Medicine® and Northwestern Memorial HealthCare. Northwestern Medicine® is a trademark of Northwestern Memorial HealthCare, used by Northwestern University |

- Home

-

Specialties

-

Cardiovascular

>

-

Research

>

- Improving Risk Prediction in Pregnancy-related Hypertensive Disorders

- Understanding Inflammation in the Heart

- Novel Drug May Improve Oxygen Uptake in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

- The Connection Between Diabetes and Heart Disease

- Socioeconomic Status and Readmission After Acute Type A Aortic Dissection Repair

- Research Insights on Diagnosing Cardiac Sarcoidosis and Treating Recurrent Pericarditis

- Weight Loss Drug Shows Benefits for Heart Failure

- Highlights From the 2024 American College of Cardiology Annual Meeting

- Feinberg Investigators Lead AHA Heart Disease Research Initiative

- The Role of Research and Exercise Testing in HFpEF Care

- ‘Polypills’ Can Help Patients Reduce Heart Disease Risk

- Treating Cardiovascular Health with Anti-Obesity Medications and Addressing Health Equity

- A Closer Look at Research Honored at STS 2024

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

- Challenging Case: Addressing a Rare Congenital Condition

- Pericardial Disease: Its Prevalence and the Role of Multidisciplinary Care

- Behind BCVI: The Benefits of Health System Integration

- Behind BCVI: An Overview of PTE With Dr. Chiu

- The Role of AI and Pulsed Field Ablation in AFib Management

- How Burnout, End-of-Life Issues and Teamwork Intersect in Cardiac Care

- Promoting DEI in Heart Failure Care Through an Interactive Curriculum

- Comparing Left Ventricular Venting Strategies

- Concomitant Management of AFib During Cardiac Surgery

- Innovative Treatment for AFib: Pulsed Field Ablation

- Breakthrough Tricuspid Valve Replacement With Edwards EVOQUE System

- Advances in Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery at Northwestern Medicine

- Developing a World-Class Mitral Valve Program

- Northwestern Medicine Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute Celebrates Continued Growth in Cardiac Surgery

- The AHA’s New Risk Calculator for Cardiovascular Disease

- Expanding the Innovative Team at Northwestern Medicine Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute

- Cardiac Surgeon S. Christopher Malaisrie, MD, Offers Insight on the Ross Procedure

- Stroke Prevention and Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion (LAAO) Devices at Northwestern Medicine

- ACU-Heart Clinical Trial Shows Reduction in Post-op Atrial Fibrillation

- Landmark PTE Procedure for CTEPH Completed by Northwestern Medicine Pulmonary HTN Team

- Ross Procedures Routinely Performed at Northwestern Medicine

- Northwestern Medicine Pericardial Disease Program: Vision, Diagnosis and Treatment Options

- Comprehensive Team Effort for Heart Transplantation at Northwestern

- Inside the OR: Heart Transplant

- A Look Inside the OR: Exploring “Why Northwestern Medicine”

- 'Heart in a Box' Technology Takes Flight

- Northwestern Medicine Pulmonary Embolism Response Team

- Northwestern Medicine Center for Artificial Intelligence Improving Clinical Practice

- Northwestern Medicine Cardio-Oncology Program

- “Heart in a Box” Technology Helps Northwestern Medicine Surgeons Perform a First-of-its-Kind Transplant in Illinois

- Douglas R. Johnston, MD, Joins Northwestern Medicine Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute as Chief of Cardiac Surgery

- McDermott Honored with AHA Distinguished Achievement Award

- Northwestern Scientists Tackle Common Type of Heart Disease with Novel Approaches and New Urgency

- Can Weekly Prednisone Treat Obesity?

- Smart, Dissolving Pacemaker Communicates With Body-Area Sensor and Control Network

- New Approaches for Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction With Sanjiv Shah, MD

- BAV Program at Northwestern Medicine

- Artificial Intelligence and Cardiovascular Care

- New Genetic Risk Factors for Arrhythmia Discovered

- Basic Science Research Into the Mechanisms of Atrial Fibrillation

- Northwestern Medicine Cardiac Amyloid Program

- Pursuing Deeper Understanding about the Most Common Type of Heart Failure

- Response to Exercise is Key to Novel Device Therapy for the Most Common Type of Heart Failure

- First-Ever Transient Pacemaker Harmlessly Dissolves in Body

- Advances in Atrial Fibrillation Catheter Ablation

- Left Atrial Appendage Closure and Occlusion

- Atrial Fibrillation Monitoring and Screening

- Introducing the New Northwestern Medicine Bluhm Heart Hospital

- Northwestern Selected as Home for Journal of Clinical Investigation; McNally to Serve as Editor-in-Chief

- Harnessing Artificial Intelligence to Improve Cardiovascular Care

- Using Machine Learning to Identify Patients with Advanced Heart Failure

- Northwestern Medicine Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute Celebrates 17 Years of World-Class Care

- Three Feinberg Faculty Elected to National Academy of Medicine

- Artificial Intelligence and the Development of Cardiovascular Health Care Solutions

- Lloyd-Jones Testifies in Support of Cardiovascular Health Legislation

- Clyde W. Yancy, MD, MSc, Honored by American Heart Association

- Current and Past American Heart Association Presidents at Northwestern Medicine

- What Role Does Genetic Testing Play in Cardiovascular Care?

- The Evolution of Cardiac Monitoring with Rod Passman, MD

- Salt Substitute Reduces Stroke and Heart Attacks

- Drug May Improve Cardiac Function in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

- Lloyd-Jones Named President of American Heart Association

- Northwestern Medicine Lake Forest Hospital Welcomes Renowned Vascular Surgeon John F. Golan, MD

- Tackling Inflammation to Improve Heart Attack Recovery

- Three Feinberg Faculty Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Treating Mitral Regurgitation with Transcatheter Mitral Heart Valve Procedures

- Advancements in Minimally Invasive Open Heart Valve Surgery Including Valve-in-Valve Procedures

- Heart Failure Holiday Symposium 2020: Session 1

- Treating Tricuspid Regurgitation with Transcatheter Tricuspid Heart Valve Procedures

- Proxy Measures Fail to Assess Cardiovascular Care

- Treating Aortic Stenosis with Transcatheter Aortic Heart Valve Procedures

- Recent Advancements in Open Heart Valve Surgery

- Artificial Intelligence in Echocardiography: Friend or Foe?

- Ultrasound Enhancing Agents (UEA)

- Echocardiographic Evaluation of Athletes

- Earlier Treatment May Reduce Cardiovascular Disease

- High Blood Pressure Risky, Even for Young Adults

- Gene Therapy Could Treat Atrial Fibrillation

- Heart Failure, Hypertensive Deaths Rise in Black Women and Men

- Open Heart Surgery | Inside the OR

- Determining Aspirin's Benefit for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

- Sex May Influence Effectiveness of Common Heart Failure Drug

- It's All in the Genes: Knowing Your Risk for Heart Failure

- Jonathan D. Rich, MD and Lisa D. Wilsbacher, MD, PhD - The Genetics of Heart Failure

- Jonathan D. Rich, MD and S. Christopher Malaisrie, MD - CTEPH: Challenges and Treatments

- 15th Annual Heart Failure Symposium: Highlights and Takeaways

- The Holy Grail of Healthcare: Providing the Safest, Highest Quality Care at the Lowest Cost

- Bonus Episode: Heart Healthy Tips for 2020 with Clyde Yancy, MD, and Donald Lloyd-Jones, MD

- James D. Flaherty, MD and Ranya N. Sweis, MD, MS - Low-Risk TAVR

- Patrick M. McCarthy, MD and James B. Hermiller, Jr., MD - Transcatheter Mitral Repair and Replacement

- Heart Failure: There is Excitement in the Air

- Patrick M. McCarthy, MD and Ralph Damiano Jr., MD - Minimally Invasive A-Fib Ablation

- Charles J. Davidson, MD and Rebecca T. Hahn, MD - Tricuspid Regurgitation

- David J. Mehlman, MD, and Nausheen Akhter, MD - Cardio-Oncology: The Central Role of Imaging

- Kameswari Maganti, MD and Akhil Narang, MD - Interventional Cardiology: Structural Imaging

- Kameswari Maganti, MD and James D. Thomas, MD - Strain: Exploring New Frontiers in Cardiac Imaging

- Vera H. Rigolin, MD and Jyothy J. Puthumana, MD - Tricuspid Valve: Remembering the Forgotten Valve

- James L. Cox, MD and Randolph P. Martin, MD - Lesion Set for a Surgical Maze Procedure

- Patrick M. McCarthy, MD and Randolph P. Martin, MD - Referring Patients for AFib Surgery

- Andrea Natale, MD, Randolph P. Martin, MD - First Catheter Ablation Procedure, Patient w/Persistent AF

- Bradley P. Knight, MD and Randolph P. Martin, MD: Best Candidates for Left Atrial Appendage Closure

- David E. Haines, MD and Randolph P. Martin, MD - Electroporation in Atrial Fibrillation Ablation

- Patrick M. McCarthy, MD, James L. Cox, MD and Bradley P. Knight, MD - Highlights of CAST-AF

- Susan S. Kim, MD and Randolph P. Martin, MD - The Best Device for Pulmonary Vein Isolation

- Catheter & Surgical Therapies for Atrial Fibrillation (CAST-AF) CME conference - August 2019

- Making Heart Failure Sexy

- Your Ideal Heart Health with Donald Lloyd-Jones, MD, ScM

- Predicting the Severity of Cardiomyopathy via Genetic Modifiers

-

News

>

- Introducing Behind BCVI: A New Video Series for Physicians

- Four Local Physicians Named Inaugural Recipients Of The St. George Foundation Distinguished Physician Awards

- Northwestern Medicine Experts At Heart Rhythm 2024

- Northwestern Medicine Experts At AATS 2024

- Northwestern Medicine Experts at ACC.24

- 2 Northwestern Medicine Physicians Make NMQF’s ‘40 Under 40 Leaders in Minority Health’ List

- Advancing Cardiovascular Care Through AI

- Meet Jane E. Wilcox, MD, MSc, New Associate Chief of Cardiology at Northwestern Medicine

- 2023 Year in Review | Northwestern Medicine Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute

- Launching the Northwestern Medicine Center for Aortic Care

- Meet Quentin R. Youmans, MD: Northwestern University Alumnus

- American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2023

- CARDIA Study Receives 10-Year $11 Million Grant Renewal

- 45th Annual Echo Northwestern

- Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics 2023

- 47th Annual Northwestern Vascular Symposium

- AHA "Get With the Guidelines" 2022 Awards

-

Research

>

-

Endocrinology

>

-

Clinical Breakthroughs In Endocrinology

>

- Gender-Affirming Care and Creating a Welcoming Practice

- Changing the Conversation Around Obesity

- Transforming Patient Care: Northwestern Medicine's Trailblazing Approach to CGM in Epic

- GLP-1 Agonists for Weight Loss with Robert Kushner, MD

- InDiscussion Series on Obesity with Robert Kushner, MD

- Uncovering the Risks of Essential Metal Supplements on Diabetes

- Why Late-Night Eating Leads to Weight Gain, Diabetes

- Endocrinology Diabetes

- Stepwise Approach to Continuous Glucose Monitoring Interpretation for Internists and Family Physicians

- Diabetes Drug Metformin Shows Potential Benefit in Large COVID-19 Trial

- Grant Barish, MD Elected to ASCI

- Diabetes Requires a Village: Northwestern Medicine's Diabetes Tune-Up Pathway Program

- New Function for Glucose Metabolism Enzyme

- Exposure to Artificial Light During Sleep May Increase Risk of Heart Disease and Diabetes

- Northwestern Investigates COVID-19: Antibodies, Global Surveillance, Women in Research

- Glucocorticoids Enhance Muscles Through Sex-Specific Pathways

- Attacking an Epidemic From All Angles

- Northwestern Study Honored by Clinical Research Forum

- Nanotherapy Offers New Hope for the Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes

- Research: Energy State to Transcription during Time-Restricted Feeding

- Gestational Diabetes

- Reflections on the Growing Field of Obesity Medicine

- Modern Malady

- Enhanced Autophagy Could Help Treat Diabetes

- New Technologies in Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Hybrid Closed Loop Systems

- New Anti-Obesity Medication Almost Twice as Effective as Most Currently Approved Weight-Loss Drugs

- Emerging Treatments for Osteoporosis and Osteopenia

- Multi-Faceted Therapeutic Target for Metabolic Syndrome Discovered

- Precision Medicine Approaches for Aggressive Forms of Thyroid Cancer

- A Promising Obesity Drug with Robert Kushner, MD

- Drug Proves Ineffective in Slowing Diabetic Kidney Disease

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring May Help Reduce Hypoglycemia

- The Latest in Continuous Glucose Monitoring Technology

-

Research In Endocrinology

>

- GRAZIA ALEPPO, MD DISCUSSES INHALE-3 TRIAL AND DIABETES TECHNOLOGY UPDATES AT ADA 2024

- Discovery Could Lead To New Therapeutic Strategies For Diabetes

- Nearly 40% of Type 2 Diabetes Patients Stop Taking Their Second-Line Medication

- New Study Uncovers BCL6 Gene’s Crucial Role in Muscle Mass Maintenance

- Transcription Factors Influence Insulin-Producing Beta Cells

- Efficacy And Safety Of Semaglutide 2.4 Mg According To Antidepressant Use At Baseline: A Post Hoc Subgroup Analysis

- Study Finds Antidiabetic Drug Effective for Weight-Loss

- Christina Coventry, RN, Provides Insight Into Clinical And Research Nursing Support

- Epidemics of Obesity and Diabetes

- Diabetes and Disparities in Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Community Healthcare Settings

- Asian Americans’ Obesity Prevalence is not One-Size-Fits-All

- Inhibiting a Metabolic Regulator in Specialized Immune Cells Increases Inflammation

- Northwestern Scientist Takes Top Honors from Clinical Research Forum

- Research Explains Why Time of Day Affects Efficacy of Interventions in Type 2 Diabetes

- Combination Use of Insulin for Treatment of Pre-Existing Type 2 Diabetes in Pregnancy

- P2Y1 Purinergic Receptor Identified as a Diabetes Target in a Small-Molecule Screen to Reverse Circadian β-cell Failure

- Research: Nutrition and Weight Management with Semaglutide

- Investigators Identify New Connections Between Circadian Rhythm and Muscle Repair

- Iron Accumulation Linked with Age-Related Cognitive Decline

- Genetic Research Findings of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) with Margrit Urbanek, PhD

- Understanding Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) Diagnosis with Margrit Urbanek, MD

- Study Identifies Expanded Role for Metabolic Enzyme in Kidney Cancer

- Cadmium-Mediated Pancreatic Islet Transcriptome Changes in Mice and Cultured Mouse Islets

- Study Explores Human Energy Expenditure Over the Lifespan

- Black and Mexican American Adults Develop Diabetes at a Young Age

- 'Alarming' Rise in Gestational Diabetes in U.S.

- New Role for RNA Splicing in Insulin Regulation

- Compound Influences Age-Related Decline in Circadian Rhythms

- Examining the Molecular and Metabolic Underpinnings of Appetite Regulation

- Understanding the Role Transcription Factors Play in Obesity

- Unraveling the Connection Between Circadian Rhythm and Hunger

- Examining the Molecular and Metabolic Underpinnings of Appetite Regulation Podcast

-

News

>

- 84th ADA Scientific Sessions

- Northwestern Medicine Experts At The Endo 2024 Annual Meeting

- Northwestern Medicine’s Chelsea Hepler Receives 2024 Pathway to Stop Diabetes Grant

- 2023 Year in Review | Northwestern Medicine Endocrinology

- Patient and Physician Reflect on 10 Years of Care in Glenview and Deerfield

- Grazia Aleppo, MD, Presents at the 2023 American Diabetes Association Annual Meeting

- Northwestern Medicine at ENDO 2023

- 2022 Year in Review | Northwestern Medicine Endocrinology

- Joseph Bass, MD, Received A 2023 Laureate Award From The Endocrine Society, And A 2023 Sleep Research Society Award

-

Clinical Breakthroughs In Endocrinology

>

-

ENT (Otolaryngology)

>

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

- Advances in Rhinology and Chronic Sinusitis

- Advances in Otology and Neurotology Research

- The Changing Epidemiology of Oral Cavity Cancer

- The Truth About At-Home Food Sensitivity Tests: A Critical Discussion With Melissa Watts, MD

- Advances in Laryngological Head and Neck Surgery at Northwestern Medicine

- ‘Peanut Patch’ May Help Desensitize Allergic Toddlers

- The Future of IgE-Mediated Allergy Research and Treatments

- HPV-Related Head and Neck Cancer: The Silent Threat

- Understanding the Immune System with Stephanie Eisenbarth, MD, PhD

- Why Are Food Allergies on the Rise? with Ruchi Gupta, MD, MPH

- Northwestern Launches New Center for Human Immunobiology

- New Tool to Create Hearing Cells Lost in Ages

- Upper Airway Stimulation for CPAP-Resistant Sleep Apnea

- Re-Examining Antibodies’ Role in Childhood Allergies

- Robotic Surgery for Head and Neck Cancer at Northwestern Memorial Hospital

- Addressing a Hidden Epidemic: Chronic Rhinosinusitis

- Regan Thomas, MD, Using Plastic Surgery to Help Complicated Head and Neck Cancer Cases

- Regan Thomas, MD, Using Plastic Surgery to Treat Head and Neck Cancer Patients

- Advances in Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer

-

Research

>

- Whitney Stevens, MD, PhD, Honored With ASCI Young Physician-Scientist Award

- Understanding How Aggressive Thyroid Cancer Evolves

- Anaplastic Transformation in Thyroid Cancer Revealed by Single-Cell Transcriptomics

- First Wearable Device for Vocal Fatigue Senses When Your Voice Needs a Break

- Childhood Hearing Loss with Nancy M. Young, MD

- Investigating Protein’s Role in Hearing Loss

- Management Paradigms for CRS in Individugals with Asthma: An Evidence-Based Review

- The EUFOREA Pocket Guide for Chronic Rhinosinusitis

- Synergy of Oncostatin M and IL-4 in Inducing TSLP Expression in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps

- Changing Epidemiology of Oral Cavity Cancer in the United States

- The Pathological Mechanisms of Hearing Loss Caused by KCNQ1 and KCNQ4 Variants

- Patient Perspectives on the Drivers and Deterrents of Antibiotic Treatment of Acute Rhinosinusitis

- Studies on activation and regulation of the coagulation cascade in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

- Consensus of Free Flap Complications: Using a Nomenclature Paradigm in Microvascular Head and Neck Reconstruction

- Clinical and Economic Burden of CRSwNP: A U.S. Administrative Claims Analysis

- Improvement in Patient-Reported "Taste" and Association with Smell in Dupilumab-Treated Patients with CRSwNP

- Mepolizumab for CRSwNP: In-depth Sinus Surgery Analysis

- Retinoic Acid Promotes Fibrinolysis and May Regulate Polyp Formation

- Persistent Discharge or Edema After Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis are Associated with a Type 1 or 3 Endotype

- Efficacy of an Oral CRTH2 Antagonist in the Treatment of Chronic Rhinosinusitis

- Strong and Consistent Associations of Precedent Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Risk of Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis

- Prognostic Factors for Polyp Recurrence in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps

- Anti-Phospholipid Antibodies are Elevated and Functionally Active in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps

- CRS-PRO and SNOT-22 Correlations with Type 2 Inflammatory Mediators in Chronic Rhinosinusitis

- Endotypes of Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Relationships to Disease Phenotypes, Pathogenesis, Clinical Findings, and Treatment Approaches

- Evaluating Dysphagia and Xerostomia Outcomes following Transoral Robotic Surgery for Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer

- Childhood Hearing Loss with Nancy Young, MD

- Researchers Investigate Elevation of Activated Neutrophils in Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps

- Genome-Wide Association Studies Reveals Context-Specific Genetic Mechanism at a Childhood Onset Asthma Risk Locus

- The Role of Biologic Therapies in the Treatment of Severe Rhinosinusitis

- Critical Function of Cilia Protein Discovered

-

News

>

- Advanced Training in Open and Endoscopic Surgery: A Hands-on Skull Base CME Program

- Northwestern Medicine Otolaryngology 2023 Year in Review

- Nancy M. Young, MD Gives the 2023 Howard P. House, MD Memorial Lecture for Advances in Otology

- Advanced Training in Open and Endoscopic Surgery: A Hands-on Skull Base CME Program

- Medical School Faculty Named AAAS Fellows

- Thomas Named President-Elect of Illinois State Medical Society

- Northwestern Medicine Launches Division of Sleep Surgery

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

-

Gastroenterology

>

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

- Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders: From Esoterica to Clinical Practice

- GERDBot™ Gives Patients Faster Care

- Investigating Methods for Preventing Pancreatitis after Endoscopy

- Beyond Surgery: Organ-Sparing Strategies for Patients With Rectal Cancer

- Putting Constipation Into Context

- Advanced Approaches to IBD Care: A Conversation with Northwestern Medicine Experts

- Transplant Oncology: Current Trends and Future Directions for Physicians

- Engineered Probiotic Can ‘Sense’ Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Comparing Weight Loss Modalities: Medical vs. Surgical

- Northwestern Medicine Introduces Warm and Cold Liver Perfusion for Liver Transplants

- How to Prepare for the Upcoming GI Fellowship Season

- Northwestern Memorial Hospital Performs 2,500th Liver Transplant Surgery

- Northwestern Medicine Approaches for Gastroparesis

- Northwestern Medicine Gastroenterology Department Leads in Global Health Education

- Treatment for Barrett's Esophagus

- Frailty Linked to Worse Quality of Life After Liver Transplant

- Multidisciplinary Approach to IBD Surgery at Northwestern Medicine

- Complex Case Report: The First Combined Lung-Liver Transplant at Northwestern Medicine

- New Service at Central DuPage Hospital Brings World-Class Liver Care to Chicago Suburbs

- Northwestern Medicine's Fecal Microbiota Transplant Program

- New Global Efforts and Equity Focus of the Northwestern Medicine Liver Transplant Program

- Northwestern Medicine Builds Team of National Leaders in Hepatology

- Nanoparticles in Liver Disease

- Updates in Robotic Cholecystectomy

- Biologic Therapies for IBD

- Crohn’s Antibodies Equally Effective

- GI Psychology and the Brain-Gut Connection

- Advanced Robotics for Colorectal Surgery

- Levitsky Selected as President-elect of American Society of Transplantation

- Intensive Crohn’s Treatment is Safe

- Surgery for GERD

- Updates in Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Syndromes

- Scientists Identify Proteins That Could Predict Liver Transplant Rejection

- How Is Artificial Intelligence Transforming Treatment of Gastrointestinal Diseases?

- Gastrointestinal Surgical Technique Linked to Lower Recurrence of Cancer

- Updates in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- FLIP Panometry on Endoscopy: Can It Be a Manometry Alternative?

- New Drug Effective in Ulcerative Colitis

- Utility of Biomarkers of Rejection and Kidney Injury in Tailoring Liver Transplant Immunosuppression

- Evaluating Colonoscopy Retroflexion in Practice

- Esophageal Diseases, Symptom Anxiety and Hypervigilance with John Pandolfino, MD

- Miller Receives Biomaterials Award for Celiac Disease Nanoparticle Therapy

- Evaluating Esophageal Hypervigilance and Symptom Anxiety

- Northwestern Medicine Experts at DDW 2021 Virtual

- Anxiety's Overlooked Role in Swallowing Disorders

- Clinical Management of Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Syndromes

- Cirrhosis: Is Liver Transplantation Always Needed?

- Wireless Monitoring Informs Acid Reflux Therapy

- Gastrointestinal Robotic Surgery: Developments and Perspectives

- Bariatric Surgery: Preoperative Evaluation, Optimizing Outcomes and More

- Managing Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

- Optimizing Biologic and Conventional Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Treating GERD with Dietary Therapy

- Food-Related Quality of Life in Patients with IBD and IBS

- A Multidisciplinary Approach for Functional Bowel Disease Treatment

- The Link Between Heartburn and Esophageal Cancer

- Considerations for the Management of Achalasia

- Novel Injectable Therapy Shows Promise in Treating Crohn's Disease

- Updates in Endoscopic Interventions: A Look at POEM and ESD

-

Research

>

- Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis

- Prospective Study of an Amino Acid-Based Elemental Diet in an Eosinophilic Gastritis and Gastroenteritis Nutrition Trial

- Using Physiology to Predict Treatment Response in Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- Artificial Intelligence Helps Northwestern Medicine Gastroenterologists Detect and Remove 13% More Colorectal Polyps

- More Than 60% of Crohn's Patients Sustained Remission with Subcutaneous Biosimilar CT-P13

- Human Models Offer New Insights Into IBD

- Parambir S. Dulai, MD, Awarded $25,000 Sherman Emerging Leader Prize

- Leading Translational Gastroenterology Research

- Genetics of Eosinophilic Colitis Revealed

- The Molecular Side of Esophageal Diseases

- Study Reveals Potential Therapeutic Target for Genetic Liver Disease

- Black Patients With Cirrhosis Have Higher Mortality Rates

- Anti-Siglec-8 Antibody for Eosinophilic Gastritis and Duodenitis

-

News

>

- Northwestern Medicine Announces the Kenneth C. Griffin Esophageal Center to Improve the Lives of Patients with Esophageal Diseases

- John Pandolfino, MD Honored with AGA Distinguished Mentor Award

- DDW 2024

- 2023 Year in Review | Northwestern Medicine Gastroenterology

- AASLD The Liver Meeting® 2023

- Liver Transplantation: Challenges and Advances in the 21st Century

- Eric Hungness, MD, Leads Make-A-Wish Participant Through a Day as a Physician

- Dinner With An Expert: A Virtual CME Series

- DDW 2023

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

-

Geriatrics

>

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

- Northwestern Medicine Geriatrics Home Care Program

- Negotiation and Dispute Resolution: A GeriPal Podcast with Lee Lindquist, MD, MPH, MBA and Alaine Murawski

- NegotiAge: An AI-Powered Negotiation Solution

- Planyourlifespan.org Celebrates 10 Years of Improving Geriatric Planning

- "Sandwich Generation" | Analysis on Reducing Caregiver Burnout while Caring for 2 Generations

- Epigenetic ‘Age’ Predicts Cognitive Function

- AGS22 Recap: Dr. Lindquist and Dr. Bradley on Twitter Spaces Live

- New Tool to Create Hearing Cells Lost in Aging

- Transitional Care Practice Reduces Costs

- Caregiver Involvement in Older Adult Medication Management

- Allison Schierer Wins the AGS 2022 Presidential Poster Award

- Lee Lindquist, MD, MPH Honored with Choosing Wisely® Champion Award and with a Faculty Selection by AMDA

- Northwestern Investigates COVID-19: Antibodies, Global Surveillance, Women in Research

- Population Aging and Global Health with June McKoy, MD, MPH, JD, MBA, LLM

- Director of Center for Aging and HIV: Increasing Patient Lifespan and ‘Healthspan’

- Negotiating with Older Adults Program Coming Soon

- Sara M. Bradley, MD, Recognized for Exceptional Commitment to Geriatrics

- Proactivity and Partnership: How The Geriatrics Team Mitigated COVID-19's Impact On The Nursing Home

- Medical Student Volunteers for Senior Social Calls Program

- Using Voice-Controlled Personal Assistants to Reduce Social Isolation

- 2021 American Geriatric Society Annual Scientific Meeting Highlights

- Geriatric Emergency Departments Associated with Lower Medicare Expenditures

- Addressing Conflicts Surrounding Older Adult Social Need Through Negotiation Training

- New Center Tackles Primary Care for Older Adults

- Improving Memory Loss in Older Adults with Joel Voss, PhD

- Providing Effective Cancer Care for Geriatric Patients

- Using Artificial Intelligence to Support Seniors Aging in Place

- Improving Geriatric Patient Outcomes with Home Care Programs

- Medication Management in Geriatric Care

- Humor Doesn't Retire

-

Research

>

- STUDY SHEDS LIGHT ON EMERGENCY CARE FOR DEMENTIA PATIENTS

- Study Shows Caregivers with Low Health Literacy Struggle with Health Tasks

- Greater COVID-19 related stresses among adults with chronic conditions

- Investigating the Medication Profile of SuperAgers

- New NIH Grant to Study Caregiver Networks of Older Adults with Alzheimer's Disease

- GSA 2023 Annual Scientific Meeting

- What Matters Most in Geriatric Care: The 5 M's of Age-Friendly Health Care

- The Roles of Busyness and Daily Routine in Medication Management Behaviors Among Older Adults

- A Mastery Learning Approach to Education About Fall Risk and Gait Assessment

- Dissemination of a Long-Term Care Planning Tool

- Social Justice and Equity: Why Older Adults With Cancer Belong-A Life Course Perspective

- Determining What Matters Most to Hospitalized Patients: A Qualitative Analysis

- Development and Pilot Testing of EHR-nudges to Reduce Overuse in Older Primary Care Patients

- Aspects of Cognition That Impact Aging-In-Place and Long-Term Care Planning

- Key Recommendations from the 2021 "Inclusion of Older Adults in Clinical Research" Workshop

- Implementation of an Antibiotic Stewardship Program in Long-term Care Facilities Across the US

- Declining Heart Health in Most Pregnant Women with Sadiya Khan, MD, and Natalie Cameron, MD

- Iron Accumulation Linked with Age-Related Cognitive Decline

- Direct-to-Caregivers Research Dissemination: A Novel Approach to Targeting End-Users

- Improvement in Self-Efficacy among Older Adults Aging-in-Place during COVID-19

- Geriatric Knowledge Gaps of Community-Based Providers: A National Study of Asked Questions

- Choosing Unwisely: Dissemination Needs of Primary Care Providers of Patients with Alzheimer's Disease

- Biomarker Predicts Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer’s Disease

- Neuropsychological Profiles of Older Adults with Superior versus Average Episodic Memory: The Northwestern "SuperAger" Cohort

- No Pain, No Gain in Exercise for Peripheral Artery Disease

- Investigators to Explore Circadian Rhythms in Cancer and Aging

- Wayne and McDermott Honored for Contributions to Medical Education, Research

- Investigating the Biology of Aging

- Dark Chocolate and Peripheral Artery Disease with Mary McDermott, MD

- What Makes Someone a SuperAger? with Emily Rogalski, PhD

-

News

>

- 2023 Year in Review | Northwestern Medicine Geriatrics

- Dr. June McKoy Named to NCCN Forum on Diversity, Equity & Inclusion- Geriatrics

-

Geriatrics Grand Rounds Series

>

- The Journey to Age Friendly

- Building Capacity to Optimize Health for Older Adults with Kidney Disease

- Geri-a-FLOAT: A Sustainable Model of Learning & Support During a Pandemic

- Teaching Geriatrics Outside the Hospital

- Home Healthcare Workers’ Contributions to Patient Care in Heart Failure: Leveraging a Previously Overlooked Workforce

- Progress Report: Highlights from McGaw Geriatrics

- Geroscience Academy Grand Rounds >

- McGaw Medical Center 2022-2023 Fellow: Harsimran Singh, MD

- Northwestern Medicine Geriatrics Welcomes Eliana Geller, DO

- 2022 Year in Review | Northwestern Medicine Geriatrics

- Northwestern Medicine American Geriatric Society 2023

- Dr. June McKoy Appointed to Assistant Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- New Potocsnak Longevity Institute Aims to Lengthen ‘Healthspan’

- Northwestern Medicine American Geriatric Society 2022

- Northwestern Medicine Announces the Division of Geriatrics

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

-

Nephrology

>

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

- First Device to Monitor Transplanted Organs, Detect Early Signs of Rejection

- CJASN 2021 Editors' Choice Articles Recognizes Publication by Northwestern Medicine’s Park and Friedewald

- Home Hemodialysis Program at Northwestern Medicine

- Quaggin Elected to National Academy of Inventors

- The Northwestern Medicine African American Transplant Access Program with Dinee Simpson, MD

- Examining the Long-Term Health of Living Kidney Donors

- Quaggin Selected to Lead American Society of Nephrology

-

Research

>

- Transcription Factor Prevents Bone Frailty in Chronic Kidney Disease

- Michael Donnan, MD, Receives Young Investigator Grant to Study Protective Mechanisms of Lymphangiogenesis in Kidney Injury

- Northwestern Medicine Nephrologists Awarded New R01 Grants

- AHA Names Quaggin a Distinguished Scientist

- Study Shows Cell Membrane-Bound Enzyme is Essential for COVID-19 Infection

- Ahya Honored with Service Award from National Kidney Foundation

- Cardio-Kidney Trials Present Obstacles - Nephrology

- The Importance of Kidney Health for Heart Health

- Catalyzing Discoveries to Treat Kidney Disease

- Exploring Molecular Mechanisms of Kidney Disease

- Study Reveals Molecular Mechanisms Behind Genetic Kidney Disease

- Bioengineered Organs and Kidney Diseases with Susan Quaggin, MD

- News >

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

-

Neurosciences

>

- Rare and Complex Brain Tumors

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

- Case Report: A One-In-a-Million High-Risk Colloid Cyst

- What’s the Fuss with FUS? Focused Ultrasound for Essential Tremor

- Drug Reprograms Immune Responses to Target Glioblastoma

- From Brain to Liver: Advances in Wilson Disease Management

- Seizure Solutions: Inside a Specialized Clinic for First Seizures

- Case Report: Lumbar Disc Herniation and Lumbar Radiculopathy

- Case Report: Failed Back Syndrome

- Case Report: Complex Spinal Fusion for Parkinson’s Disease-Related Kyphosis

- Q&A With Elizabeth Gerard, MD: Guiding Your Patients With Epilepsy Through Pregnancy

- New Drug Shows Promise for Treating Rare Brain Tumors

- Using Gene Expression Profiling to Predict Meningioma Outcomes and Guide Adjuvant Radiotherapy Decisions

- Rituximab and Pregnancy: Late-Onset Neutropenia in a 2-Month Infant Whose Mother Received Rituximab 2 Weeks Prior to Childbirth

- Understanding and Preventing Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy

- Comparing Cardiac Monitoring Methods to Detect Atrial Fibrillation After Stroke

- Using Gene Expression to Predict if a Brain Tumor is Likely to Grow Back

- Novel Therapy Extends Survival in Metastatic Cancer

- Microvascular Decompression for Trigeminal Neuralgia

- Case Report: Tic Disorder in an Adult

- Shedding Light on Primary Vitreoretinal Lymphoma

- Improvisatory Music Calms Epilepsy Patients

- Leqembi: What Physicians Need to Know About the New Alzheimer’s Drug

- Northwestern Medicine Collaborates With The Joffrey Ballet to Launch “Dancing With Parkinson’s”

- Combination Treatment May Help Some Patients With Glioblastoma

- Case Challenge: A 51-Year-Old With New Onset Seizures

- Managing Adult Scoliosis: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment Insights for Primary Care Physicians

- Dizziness: A Neuro-otologic and Neuro-ophthalmic Approach

- Developing New Nanoparticle Treatments for Brain Tumors

- Reducing Seizures After Brain Tumor Treatment

- Investigators Identify Mechanisms Behind Chemotherapy Resistance

- Chemotherapy Drug Reaches Brain in Humans for First Time

- Combination Treatment Extends Progression-Free Survival in Brain Cancer

- Clinical Management of Low Grade Glioma

- Case Report: FIRES in 20-Year-Old College Athlete

- Predicting Risk of Blood Clots in Brain Tumors

- Endoscopic Endonasal Transsphenoidal Resection of Pituitary Adenoma for Cushing's Disease

- Case Challenge: Progressive Muscle Weakness, Pain in 68-Year-Old

- Robotics and Artificial Intelligence in Spine Surgery

- What’s New in Huntington’s Disease

- Von Hippel-Lindau Disease: Clinical Update and New Drug Therapy

- Experimental Therapies for Early Parkinson’s Disease

- Dissolving Implantable Device Relieves Pain Without Drugs

- Case Report: Endoscopic Transcervical Odontoidectomy for Basilar Impression

- Recurring Brain Tumor Growth is Halted with New Drug

- Music-Based Medical Interventions with Borna Bonakdarpour, MD

- Chordoma: En Bloc Resection and Other Management Strategies

- Approach to Focal Epilepsy Secondary to Dominant Temporal Low Grade Gliomas

- Evolution in Meningioma Classification and Management

- Higher Doses of Anti-Seizure Medications May Be Needed in Pregnancy

- Exposure to Artificial Light During Sleep May Increase Risk of Heart Disease and Diabetes

- Invasive EEG Monitoring: Stereo EEG and Defining the Epileptic Zone

- Rare Central Nervous System Tumors: Progress in Clinical Care and Research

- Multiple Sclerosis and Pregnancy

- Diagnosis and Management of Pituitary Adenomas

- Advancing Surgical Management of Epilepsy

- Neural Stem Cell Therapy May Improve Metastatic Cancer Survival

- Improving Pre-Surgical Workups for Epilepsy

- Meningioma: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment

- Predicting Which Glioblastoma Patients Will Respond to Immunotherapy

- DNA Methylation Profiling: A Groundbreaking Diagnostic Tool for Brain Tumors

- DNA Methylation Profiling in the Diagnosis of Brain Tumors

- A Look at Transverse Myelitis

- Moyamoya Disease: Etiology, Diagnosis, Treatment

- Aducanumab: What Neurologists Should Know

- Reconstruction for Brachial Plexus Injury

- Minimally Invasive Cranial and Endoscopic Skull Base Surgery

- Anti-Seizure Medication Exposure in Pregnancy Doesn’t Harm Child’s Cognitive Outcomes

- Immunotherapy for Brain Tumors

- Clinical Update: Low Grade Glioma

- Patients Need Monitoring for Atrial Fibrillation After Ischemic Stroke

- Importance of Spinal Stabilization in Spinal Cord Patients

- Three Feinberg Faculty Elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Northwestern Scientists Discover Potential Therapeutic Target for Glioblastoma

- Antibody Bolsters Immune Response to Glioblastoma

- Exploring Treatment Options for Cervical Myelopathy

- New Spherical Nucleic Acid 'Drug' Kills Tumor Cells in Humans with Glioblastoma

- Northwestern Drug Kills Glioblastoma Tumor Cells with Priya Kumthekar, MD

- Study Identifies New Potential Therapeutic Approach for Glioblastoma

- Drug for Advanced Parkinson’s Shows No Benefit

- New Therapeutic Prospect for ALS

- Wireless Device Improves Real-Time Monitoring of Blood Flow, Oxygenation in the Brain

- Neurological Management of Von Hippel-Lindau Disease

- Music Intervention for Alzheimer’s, Dementia and other Neurological Conditions

- New Brain Tumor Imaging Detects Smaller Tumors Sooner

- Ketogenic Diet Therapy for Epilepsy

- Utilizing B-Cells to Promote Glioblastoma Immunity

- Advancing Deep Brain Stimulation for Movement Disorders

- Advancing Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s

- Diagnosing and Treating Trigeminal Neuralgia

- Specialized Immune Cells May Improve Early Detection of Parkinson’s Disease

- Improving Memory Loss in Older Adults with Joel Voss, PhD

- An Update on Migraine Headache

- Reducing Dangerous Swelling in Traumatic Brain Injury

- Novel Brain Mapping Technology Outperforms Current Platforms

- Therapeutic Options for Patients with Functional Movement Disorders

- Noninvasive Brain Stimulation May Lead to New Treatments for Psychiatric Disorders

- Genetics Offers New Therapeutic Opportunities for Parkinson’s Disease

- ‘Soft’ Symptoms Detected Before Parkinson’s Disease

- New Research and Treatment of ALS

- New Interdisciplinary Neuroinfectious Disease Program to Improve Patient Care

- Immunotherapeutic approaches for treatment of glioblastoma show promise

- Investigating New Glioblastoma Therapies with Rimas Lukas, MD

- Stem Cells: A Therapeutic Approach for Brain Tumors

- New Ways to Diagnose Sleep and Circadian Rhythm Disorders with Phyllis Zee, MD, PhD

- Hispanic Brain and Spine Tumor Program at Northwestern Memorial Hospital

- Hispanic Brain and Spine Tumor Program at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (en Espanol)

- Dr. Wolinsky discusses treatments of spinal tumors

- A New Way to Diagnose Glioma Brain Tumors

- Novel Drug May Improve Treatment for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

-

Research

>

- New Glioblastoma Treatment Reaches Human Brain Tumor and Helps Immune Cells Recognize Cancer Cells

- New Mechanisms Underlying Tumor Variety in Brain Cancers Discovered

- Study Discovers Potential Biomarkers of Environmental Exposures in Parkinson’s Disease

- Practical Considerations for Managing Pregnancy in Patients With MS: Dispelling the Myths

- Uncovering the Culprits of Neurodegenerative Disorders

- Probing Deeper to Understand Protein Expression in Neurons

- Investigating Mechanisms of Aggressive Glioblastoma Tumor Growth

- Evaluating Outcomes of Extended Thrombolytic Therapy for Ischemic Stroke

- Novel Immune Inhibitor Associated with Glioma Progression

- Innate Immune Cells Promote Growth of Blood Vessels in Colon Cancer

- Mutation Provides Insights Into Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s Disease

- The Northwestern Medicine Comprehensive COVID-19 Center: A Patient’s Perspective

- Immune Genes Are Altered in Alzheimer’s Patients’ Blood

- New Anti-Blood Clotting Drug May Lower Risk of Recurrent Strokes

- New Cause of Neuron Death in Alzheimer’s Discovered

- Novel ‘Feeding’ Mechanism Promotes Glioblastoma Treatment Resistance

- Discovering New ALS Therapeutic Avenues with Evangelos Kiskinis, PhD

- A Novel BRAF::PTPRN2 Fusion in Meningioma: A Case Report

- Bone Transcription Factor Controls Nervous System Gene Expression

- New Therapeutic Strategies for Spinal Muscular Atrophy

- Phase 2 Trial Evaluates Safety and Efficacy of Factor XIa Inhibition With Milvexian for Prevention of Secondary Stroke

- Investigating the Pathogenesis of Rare Congenital Nerve Disorder

- Studies Identify Novel Underpinnings of Genetic ALS

- Study Identifies Genetic Cause for Some Brain Tumors

- Mapping Neural Activity Patterns and Odor Perception

- Gene Linked to Glioblastoma Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Immunosuppression

- Preoperative Grading Scale to Predict Outcomes by Endonasal Versus Transcranial Approach for Tuberculum Sellae Meningioma

- Newly Discovered Trigger of Parkinson’s Upends Common Beliefs

- New Approaches for Genetic Parkinson’s Treatment

- Understanding How ALS-Linked Gene Disrupts Neurons

- 100-Year-Old Brain Mystery: What Does the Temporal Pole Do?

- New Therapeutic Target for Parkinson’s Disease Discovered

- Genetic Factors in Parkinson's Disease with Steven Lubbe, PhD

- Study Identifies Enzyme that Helps Tumors Evade the Immune System

- Calming the Destructive Cells of ALS by Two Independent Approaches

- Mature ‘Lab Grown’ Neurons Hold Promise for Neurodegenerative Disease

- New Immune Culprit Discovered in Alzheimer’s Disease

- Wireless Brain Implant Monitors Neurotransmitters in Real-time

- Genetic Testing for Epilepsy Improves Patient Outcomes

- Novel Genetic Factors Contribute to Parkinson’s Risk

- Novel Deep Learning Method May Help Predict Cognitive Function

- Study Investigates Crosstalk Between Mitochondria and Lysosomes

- Music Helps Patients With Dementia Connect With Loved Ones

- Mesulam Center receives $10.4 million grant to continue research of Primary Progressive Aphasia

- Identifying Therapeutic Targets for Chemotherapy-Resistant Glioblastoma

- Light During Sleep in Older Adults Linked to Obesity, Diabetes, High Blood Pressure

- Genetic Variants in Epilepsy Gene Identified

- Why ketamine is a speedster antidepressant

- Pet Dogs Advance Glioblastoma Research with Amy Heimberger, MD

- Potential ALS Treatment May Repair Axons Of Diseased Neurons

- Elucidating Parkinson’s Disease

- Meet the pioneers of primary progressive aphasia research

- T-Cell Interactions Vary Between Tumor Microenvironments

- Lewy Body Dementias and the Immune System

- Study Finds Dopamine Signaling Promotes Compulsive Behavior

- Identifying Novel Genetic Causes of Movement Disorders

- GP2: The Global Parkinson's Genetics Program

- ALS Therapy Should Target Brain, Not Just Spine

- Fatty Acid Length Predicts Parkinson’s Disease Risk

- Uncovering the Degenerative Basis of Parkinson’s Disease

- New Autism Biomarker Discovered in Cerebrospinal Fluid

- ‘Dancing Molecules’ Successfully Repair Severe Spinal Cord Injuries

- Combination Therapy Reduces Toxic Aggregates in Parkinson’s Disease

- $18 Million For Parkinson’s Disease Research to Study Brain Circuits Driving Symptoms

- SuperAger Study Expands Nationally With $20 Million Grant

- New Insights into the Mechanism of ALS

- Lewy Body Dementia Exacerbated by Immune Response

- Fluorescent Label Passes Through Blood-Brain Barrier

- Translational Science: Glioblastoma

- Implantable Ultrasound Blasts Potent Drug into Glioblastoma

- Brain Insult From Hypertension Discovered in Middle-Aged Adults

- Uncovering Epigenetic Mechanisms Regulating Glioma Growth

- Memory Helps Evaluate Situations on the Fly, Not Just Recall the Past

- Novel Therapy May Improve Survival for Malignant Gliomas

- Immunosuppression Drug Could Reduce Chemotherapy Resistance

- Understanding Epigenetic Regulators in Neurodevelopmental Diseases and Cancer

- Interaction of Mitochondria and Lysosomes Key in Parkinson's Disease

- Mapping Neural Connections in Parkinson's Disease

- Case Report: Genetic Testing Improves Epilepsy Treatment

- Inflammation Protection May Be Critical to Treating MS

- Conformational Switch Implicated in Neurodegenerative Diseases

- New Genetic Cause of Dystonia Revealed

- Blocking Cell Division in Glioblastoma

- Protein Variant May Have Potential as Target for Glioblastoma

- Blocking Cell Division in Glioblastoma

- Untangling Cellular Changes in Pediatric Epilepsy

- Plotting the Neural Circuitry of Appetite Suppression

- ‘Logic Circuit’ in Cochlear Neurodevelopment Identified

- New Insights into Synaptic Plasticity

- New Developments in Parkinson’s Pathology

- Can Exercise Slow Parkinson's Disease Progression? with Daniel Corcos, PhD

- Uncovering the Impact of Protein Mutations in Parkinson's

- Proteins on Neuron Surfaces Prove Pivotal for Communication

- Astrocytes Play Unexpected Role in Parkinson’s Disease

- ANA Investigates Huntington's Disease

- Study Provides Insights into the Development of Alzheimer’s

- Inflammation Linked to Alzheimer’s

- Understanding Mitochondrial Dysfunction’s Impact on Neurological Diseases

- Analyzing Plasma Can Classify Brain Tumors

- Sleep and Neurodegenerative Diseases

- New Map of Inference-Based Behavior

- Elevated Gene Expression Linked to Poor Glioblastoma Survival

- Uncovering the Cellular Mechanisms Behind Genetic Mutations in ALS

- Unwrapping Oligodendrocyte Development

- Postmortem studies shed light on why GBM is so fatal

- New Migration of Brain Tumor Discovered

- How Noninvasive Brain Simulation May Enhance Long-Term Memory

- Playing Sports for Quieter Brains with Nina Kraus, PhD

- What Causes ALS? with Robert Kalb, MD

- What Makes Someone a SuperAger? with Emily Rogalski, PhD

-

COVID-19 and Neurosciences

>

- COVID-19 and Neurosciences Page 2

- Igor Koralnik, MD, and Sherry Chou, MD, Join the BioVie Advisory Board for Bezisterim in Long COVID

- What We’ve Learned Treating 4,000 Patients With Long COVID-19

- New Research Suggests Millions of People Who Tested Negative For COVID-19 May Have Long COVID

- First COVID-19 Vaccination Can ‘Hurt’ Subsequent Boosters

- Neurologic Manifestations of Long COVID-19 Differ Based on Acute COVID-19 Severity

- Novel Monoclonal Antibody Therapy for SARS-CoV-2

- Clinical Guidelines: Acute, Long-Term Neurologic Manifestations of COVID-19

- Persistent Viral Shedding Of COVID-19 Is Associated With Delirium And Six-Month Mortality In Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients

- Most COVID-19 ‘Long Haulers’ Continue to Experience Symptoms 15 Months After Initial Infection

- New Study Finds Plasma Biomarkers of Neuropathogenesis in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients and Those With Long COVID

- First-of-Its-Kind Study Finds 81% of Non-hospitalized COVID-19 'Long-Haulers' Experienced Brain Fog

- Northwestern Medicine Study Finds History of Neurological Disorder Increases Risk of Hospital Reencounter After COVID-19

- Northwestern Medicine Introduces Comprehensive COVID-19 Center to Treat Chronic COVID Disease

- Examining the Frequent Neurologic Manifestations and Encephalopathy-Associated Morbidity in COVID-19 Patients

- Neurological Complications of COVID-19 with Igor Koralnik MD

- Igor Koralnik, MD, Discusses the Impact of COVID-19 on the Central and Peripheral Nervous System

- Edward Manno, MD, Summarizes Emerging Evidence of Neurological Manifestations of COVID-19

- COVID-19 and Use of CPAP

- COVID-19: Neurological Impact and Considerations

-

News

>

- Updates in Neurology Symposium

- Alumni Spotlight: Drew A. Spencer, MD, 17’ GMER

- Drew Spencer, MD: Inaugural Recipient of the St. George Corporation Distinguished Physician Award

- Northwestern Medicine Neurology Incoming and Outgoing Residents and Fellows 2024

- AAN 2024: Pre-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 Does Not Decrease Long COVID Severity

- Highlights From AAN 2024

- Northwestern Medicine Neurosurgery Incoming and Outgoing Residents and Fellows 2024

- Q&A With Karan Dixit, MD, Neuro-oncologist and Medical Educator

- From Troy, Michigan, to Chicago, Illinois, 2 Friends Trade in Cross-Country Jerseys for White Lab Coats

- Northwestern Medicine Physician Is First to Use Hubly Drill

- Priya Kumthekar, MD, Receives 2023 Women in Neuro-Oncology Mid-Career Exemplary Physician Award

- 2023 Annual Updates From Northwestern Medicine Malnati Brain Tumor Institute

- 2023 Year in Review | Northwestern Medicine Neuroscience

- Krainc Elected to National Academy of Inventors

- Faculty Spotlight: Cody L. Nathan, MD, 23’ GMEF

- Northwestern Medicine Neurology and Neurosurgery Launch Innovative Fellowship Programs

- The Northwestern Medicine Neuro-oncology Team: Front and Center at SNO 2023

- Les Turner ALS Symposium Celebrates Research, Patient Care and Community

- Advanced Training in Open and Endoscopic Surgery: A Hands-on Skull Base CME Program

- Minimally Invasive Surgery for ICH: A Practical Workshop

- 13th Annual Les Turner Symposium on ALS

- Krainc Elected President of American Neurological Association

- Women Leaders and Innovators in Neurosciences

- Join Northwestern Medicine Neurology and Neurosurgery for Two CME Events

- Faculty Spotlight: Roger Stupp, MD, Renowned Neuro-oncologist

- Northwestern Medicine Neurosurgery Incoming and Outgoing Residents and Fellows

- Northwestern Medicine Neurology Incoming and Outgoing Residents and Fellows

- Northwestern Medicine’s Seventh Annual Advances in Epilepsy and EEG CME Symposium

- Malnati Brain Tumor Institute 2022 Annual Updates

- New Leadership in Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease

- Northwestern Medicine Neurology at 2023 AAN Annual Meeting

- 2022 Year in Review | Northwestern Medicine Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Les Turner ALS Symposium Unites Scientists, Community Around Research

- Northwestern Medicine Neurosurgery Welcomes New Faculty

- Dimitri Krainc, MD, PhD, Elected to the National Academy of Medicine

- Northwestern Medicine at the 2022 SNO Annual Meeting

- ANA2022

- Third Annual Northwestern Medicine Comprehensive Stroke and Cerebrovascular CME Conference

- Creating a Comprehensive COVID Center at Northwestern Medicine

- Celebrating Alzheimer’s Science and Clinical Care

- Northwestern Receives Distinguished Edmond J. Safra Fellowship in Movement Disorders to Train New Movement Disorder Clinician-Researcher

- Malnati Brain Tumor Institute 2022 Update

- Northwestern Medicine’s Sixth Annual Advances in Epilepsy and EEG CME Symposium

- Northwestern Medicine Neurology Welcomes Robin Buerki, MD

- Advanced Training in Open and Endoscopic Neurosurgery

- Neurosurgery 2015-2021 Report

- Pathology Chair: Evolution of Brain Tumor Classification

- Alpheus Medical Announces Formation of World-Class Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) Co-Led by Roger Stupp, MD to Support Development of Novel Treatment for Brain Cancer

- Northwestern Medicine Stroke Team Presents: Updates in Stroke and Cerebrovascular Care - a Virtual CME Series Practice Updates in Stroke Prevention

- A Year of Growth for Northwestern Medicine Neurology & Neurosurgery

- Northwestern Medicine Neurosurgery Expands Throughout Chicagoland

- Yvette Wong, PhD, Honored with NIH New Innovator Award

- Northwestern Medicine Neurology at ANA2021

- President Biden Appoints Northwestern Medicine Neurosurgeon-Scientist to National Cancer Advisory Board

- Northwestern Faculty Inducted into Prominent Medical Societies

- Wellness Curriculum May Help Decrease Residency Burnout

- PPA Conference Builds Connections in the Aphasia Field

- Zee Receives Lifetime Achievement Award from National Sleep Foundation

- Krainc to Receive $9 Million, 8-Year NIH Grant

- Les Turner Symposium Celebrates Scientific Discovery in ALS

- Cheng Named AAAS Fellow

- Northwestern Medicine Scientists Receive Multimillion-Dollar Grant to Continue Landmark Parkinson's Study

- Tour the Angiosuite with Babak Jahromi, MD, PhD

- The Next Frontier in Spine Care: Northwestern Medicine Integrated Spine Center Expands Non-Surgical Offerings to Improve Patient Outcomes

-

OB-GYN

>

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

- Comprehensive Care for Peripartum Pelvic Floor Health: The Northwestern Medicine PEAPOD Clinic

- Navigating Rare Vulvar and Vaginal Disorders With Rajal C. Patel, MD

- How Dietary Patterns Impact Ovarian Reserve and Fertility: Hear From Emily Jungheim, MD

- Treating Hepatitis C in Pregnancy and Infancy

- Medical and Surgical Approaches to Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

- Optimizing OB Workflow: Improving Access to Fetal Heart Tracings

- Enhancing Patient Outcomes in Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery

- Transforming Second-Line Immunotherapy for Endometrial Cancer

-

Parts and Labor: Roundtable Discussions with OB-GYN Experts

>

- Parts and Labor: Exploring High-Risk Pregnancies With Maternal-Fetal Medicine

- Parts and Labor: From Conception to Advocacy in Complex Family Planning

- Parts and Labor: Northwestern Medicine Advancing Uterine Fibroid Research

- Parts and Labor: Treatment Options for Uterine Fibroids and Our Multidisciplinary Approach to Care

- Parts and Labor: Disparities in Care for Uterine Fibroids

- Parts and Labor: Symptoms and Management of Uterine Fibroids

- A Physician's Role in Tackling Disparities in Reproductive Health

- Bloodless Procedure Avoids Hysterectomy: Uterine Fibroid Embolization

- Access to Fertility Treatment: The Impact of Insurance Coverage and State Mandates

- Why Northwestern Medicine Is the Ideal Destination for OBGYNs

- How The Stretch Circle Helps Surgeons at Northwestern Medicine

- Multidisciplinary Care for Complex Gynecologic Cases

- Navigating PCOS: A Multidisciplinary Approach at Northwestern Medicine

- Compassionate and Specialized Care for High-Risk Pregnancies: An Overview by Janelle Bolden, MD

- Emily Hinchcliff, MD, on Clinical Trials in Gynecologic Oncology at Northwestern Medicine

- The P2P Network: Addressing Physician Burnout

- Inside the OR: C-Section and Hysterectomy

- Teaching AI to Read Fetal Ultrasound in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- Emily Hinchcliff, MD, on the Use of Immunotherapy in Gynecologic Malignancy

- How the NURTURE Program Supports Faculty Recruitment and Equity

- Genetic Predispositions to Cancer With Gynecologic Oncologist, Dr. Jenna Marcus

- Teaching AI to Read Fetal Ultrasound in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- P2P Network: Scaling Peer Support from Pilot Project to Hospital-Wide Service

- Pathology Chair: Evolution of Brain Tumor Classification

- Genome-wide Intricacies of Cancer Inhibitor Untangled

- Successful Treatment for Uterine Fibroids

- Performing Bloodless Surgery

- The Importance of a Proactive Approach to Endometriosis

- Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Clinic at Northwestern Medicine

- Diminishing Health Inequities through Representation in Clinical Trials with Teni Brown, MD

- A Collaborative Approach to Treating Urinary Incontinence with Teni Brown, MD

- Poor Heart Health Before Pregnancy Linked to Adverse Outcomes

- Linda Yang, MD, MS, Joins the Center for Complex Gynecology

- Northwestern Medicine Named Top Hospital for Maternity Services

- Melissa A. Simon, MD, MPH, Honored With the Henry P. Russe, MD, Citation for Exemplary Compassion in Healthcare

- Trauma-Informed Care

- Melissa A. Simon, MD, MPH Elected to National Academy of Medicine

- Health Equity and the Center for Health Equity Transformation

- Dr. Roque Discusses Clinical Trials in Gynecologic Oncology at Northwestern Medicine

- Dr. Roque Discusses Gynecologic Oncology at Northwestern Medicine

- Overactive Bladder Medications and Dementia

- Scientists Develop First Wireless Sensors to Monitor Pregnant Women and Their Babies

- Advances in Fertility Preservation

- Feinberg Rises to 15th in U.S. News Ranking for Research-Oriented Medical Schools

- Complex Congenital Anomalies and the CARE Clinic

- Gynecology: Complex Vulvar and Vaginal Diseases

- Surgical Advances for Tubal Diseases

-

Research

>

- New Genes Implicated in Uterine Fibroid Development

- Study Identifies Novel Cellular Mechanisms Promoting Growth of Uterine Fibroids

- Outsmarting Chemo-Resistant Ovarian Cancer

- MDEdge: Clinical Index Predicts Common Postpartum Mental Health Disorders

- New Research Shows Limited Access to Fertility Preservation for Cancer Patients

- Northwestern Scientists Develop New Model for Understanding Uterine Fibroids

- Access to Fertility Treatment: The Impact of Insurance Coverage and State Mandates

- Combination Treatment Improves Survival in Endometrial Cancer

- Wireless Neurostimulation Safe for Urge Incontinence

- OB-GYN Research Lacks Racial, Ethnic Inclusivity

- Pregnant Gen Zers, Millennials Twice as Likely to Develop Hypertension in Pregnancy

- Northwestern Faculty Elected to Society for Clinical Trials Board

- Study Reveals Genetic Differences Among Fetal Monocytes

- Regulator of Cancer ‘Stemness’ Discovered

- Understanding Immunosuppressive Mechanisms of T-Cell Receptors

- The Power of Proximity: Effects of a Multi-Disciplinary Fibroid Clinic on Inter-Specialty Perceptions and Practice Patterns

- The Influence of a Multidisciplinary Fibroids Clinic on Uterine Fibroid Management and Inter-specialty Perceptions

- Racial Disparities in Complications and Costs After Surgery for Pelvic Organ Prolapse

- SARS-CoV-2 Infection Increases Risk of Maternal Mortality from Obstetric Complications

- Police Violence Linked to Higher Rates of Preterm Delivery, Heart Disease Among Black Women

- Declining Heart Health in Most Pregnant Women with Sadiya Khan, MD, and Natalie Cameron, MD

- Study Finds Marijuana Use Increasing Among Pregnant Individuals with HIV

- Anti-Cancer Inhibitor Could Have Dual Effect

- Supporting Women with Early Nonviable Pregnancies

- Bioinformatic Computational Tool Analyzes Tissue Samples to Discern Disease

- Research That May Impact Long-Term Fertility Outcomes

- Investigating the Genetic Mechanisms Behind Uterine Fibroids

- Gynecologic Oncology Clinical Trials

- High BMI and Pregnancy Weight Gain with Alan Peaceman, MD

- Chicago's Zip Code Issue with Melissa Simon, MD

-

News

>

- Northwestern Medicine’s Involvement in Black Maternal Health Week: A Recap

- OB-GYN 2023 Annual Report

- Northwestern Medicine American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG 2024

- Northwestern Medicine Clinicians Establish a Cervical Cancer Screening Program in the Philippines

- Northwestern Medicine and Lurie Children’s Hospital collaborate to address the unmet need of treating hepatitis C in pregnancy and infancy

- Conducting PCOS Research Study

- Survive & Thrive: An Interactive Course for Women Living With Gynecologic Cancer

- SMFM's 43rd Annual Pregnancy Meeting

- OBGYN 2022 Annual Report

- Magdy Milad, MD, Princess Urbina, MD, and NM Nurses Provide Lifesaving Care in the Philippines

- OBGYN Department Ranked Among the Best in the Nation

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

-

Oncology

>

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

- Cancer Drug Trial Provides Lessons for Future

- MRI Surveillance Significantly Reduces Breast Cancer Mortality

- Cellular Therapy Increases Survival in Recurring B-cell Lymphoma

- Treating Skin Cancer Without Risking Transplanted Kidneys in Organ Recipients

- Strengthening T-Cell Therapy for Solid Tumor Cancers

- Rethinking the Burden of Cancer Treatments’ Side Effects

- Experimental Drug May Slow Childhood Brain Tumors

- New 3D Spatial Approach Reveals Interactive View of Glioblastoma and Therapeutic Targets

- AI May Spare Breast Cancer Patients Unnecessary Treatments

- Drug Extends Survival in Prostate Cancer with Genetic Mutations

- Combination Therapy Improves Quality of Life in Advanced Stomach Cancer, Esophageal Cancer

- Novel Intercellular Signaling Mechanisms Promote Melanoma Growth

- Novel Therapy Extends Survival in Metastatic Cancer

- Improving Nanotherapeutic Vaccine Delivery

- Small, Implantable Device Could Sense and Treat Cancer

- Scientists Uncover Why Some Cells Become Resistant to Cancer Therapies

- Immunotherapy Improves Remission for Relapsed, Refractory Leukemia

- Checkpoint Inhibitor Plus Chemotherapy Improves Outcomes for Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Combining Epigenetic and Metabolic Approaches for Targeted Cancer Treatment

- Improving Cancer Detection for Women with Dense Breasts

- Improving Crystal Engineering with DNA

- New Gene Implicated in Cancer, Cellular Stress Response

- Potential Therapeutic Target for Blood Cancers Discovered

- Leading the Fight Against Lymphoma: Insights From Jane Winter, MD

- Lurie Cancer Center is Advancing Gynecologic Cancer Treatments at Northwestern Medicine

- Clinical Trials and Advances in Breast Cancer Therapy at Northwestern Medicine

- The Power of Collaboration: Lurie Cancer Center and the NCCN

- Navigating the Cancer Journey With Clinical Trials

- Innovative Approaches to Brain Cancer at Northwestern Medicine

- Transforming the Way Cancer Vaccines are Designed and Made

- Bin Zhang, MD, PhD, Named Co-Leader of Tumor Environment and Metastasis Program

- NIH Initiative to Systematically Investigate and Establish Function of Every Human Gene

- William Gradishar, MD Receives 2022 Rodger Winn Award

- New Technique Improves Proteoform Imaging in Human Tissue

- Improving Drug Therapy for Relapsed Leukemia

- Identifying Cancer Biomarkers for Immunotherapy Response

- Protein Transformation Drives Cancer Development

- Epigenetic ‘Priming’ Boosts Cancer Immunotherapy

- Deep-learning Empowers Discovery of New Genetic Mutation in Cancer

- Epigenetic ‘Age’ Predicts Cognitive Function

- Genome-wide Intricacies of Cancer Inhibitor Untangled

- Weekly Symptom Monitoring Improves Quality of Life in Cancer

- Calcium Channel Blockers May Improve Chemotherapy Response

- Cytoskeletal Proteins Interact to Form Intracellular Networks

- Deep-learning Empowers Discovery of New Genetic Mutation in Cancer

- Recurring Brain Tumor Growth is Halted with New Drug

- New Regulator of Therapy Resistance in Prostate Cancer

- New Regulator of Prostate Cancer Metastasis Discovered

- Study Identifies New Therapeutic Target for Most Common Type of Pancreatic Cancer

- Life-Changing Gene Therapy for Beta-Thalassemia Patients with Jennifer Schneiderman, MD

- Nanoparticle-Based COVID-19 Vaccine Could Target Future Infectious Diseases

- Racial and Neighborhood Disparities in Breast Cancer

- Genetic Variant of High-risk Childhood Leukemia Revealed

- Gene Therapy Promotes Transfusion Independence for Severe Beta-Thalassemia

- Tumors Dramatically Shrink With New Approach to Cell Therapy

- Novel Combination Therapy May Extend Pancreatic Cancer Survival

- Iruela-Arispe Named Co-Leader of the Tumor Environment and Metastasis Research Program

- Jane N. Winter, MD, Begins Term as American Society of Hematology President: Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University : Feinberg School of Medicine: Northwestern University

- Secondary Structures in DNA are Associated with Cancer

- Genomic Variant May Predict Cardiotoxicity From Chemotherapy

- In Cancer Treatment, Quality of Life Matters

- Cultivating Africa’s Research Enterprise

- Lurie Cancer Center Receives Merit Extension from NCI

- Anthony Yang Honored as Physician Quality Leader by the Commission on Cancer

- President Biden Appoints Northwestern Medicine Neurosurgeon-Scientist to National Cancer Advisory Board

- Critical Impact Made on Prostate Cancer Research and Care

- Lurie Cancer Center Receives Prostate Cancer SPORE from the NCI

- Managing Treatment Related Cardiovascular Side Effects

- Our Cancer Program at Northwestern Memorial Hospital Ranked No. 6 in the Nation by U.S. News & World Report

- Northwestern Medicine Leading Against Cancer

- Northwestern Drug Kills Glioblastoma Tumor Cells with Priya Kumthekar, MD

- Precision Medicine Approaches to Lung Cancer

- New Study Finds Immunotherapy Effective in Treating Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Skilled Surgeons and Colon Cancer Survival with Karl Bilimoria, MD and Brian Brajcich, MD

- Immunotherapy Effective in Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Breast and Ovarian Cancer Drug Extends Prostate Cancer Survival

- First Prostate Cancer Therapy to Target Genes Delays Cancer Progression

- Using Clinical Trials to Fight Sarcoma

- The Role of Northwestern Medicine's Lurie Cancer Center in Developing NCCN Guidelines

- Improving Survival Outcomes for Melanoma Patients

- Changes to Endometrial Cancer Treatment with Daniela Matei, MD

- Treating Agressive Prostate Cancer with Maha Hussain, MD

- Men with Agressive Prostate Cancer May Get New Powerful Drug Option

- Improving Survival for Advanced Breast Cancer with Massimo Cristofanilli, MD

-

Research

>

- Transcription Factors Cooperate to Promote Cancer Growth

- Newly Identified Protein Drives Breast Cancer Stemness and Metastasis

- Study Identifies Novel Therapeutic Target for Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- T-Cell Interactions Vary Between Tumor Microenvironments

- Investigators Identify Potential Therapeutic Target for Pancreatic Cancer

- Improving Interferon Therapy for Blood Cancers

- Regulator of Cancer ‘Stemness’ Discovered

- Optimizing Balance of Treatments in Prostate Cancer

- New Treatment for Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

- Locoregional Therapy Does Not Improve Breast Cancer Survival

- Neural Stem Cell Therapy May Improve Metastatic Cancer Survival

- Heimberger Named Interim Associate Director of Translational Research at the Lurie Cancer Center

- Histone Protein Influences Both Neurological Disorder and Cancer

- New Alternative for Relapsed B-Cell Lymphoma

- Microspheres Delay Progression of Colon Cancer

- New Insights into Cell Polarity

- Study Shows Epigenetic Modification is Central for Tumor Metastasis

- Encoding Hierarchical Assembly Pathways of Proteins

- Predicting Which Patients Will Discontinue Breast Cancer Therapy

- Anti-Cancer Inhibitor Could Have Dual Effect

- Study Identifies Expanded Role for Metabolic Enzyme in Kidney Cancer

- Advancing Treatment for B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- Skin Cancer Harbors Targetable Mutation

- Northwestern Medicine’s Brain Tumor SPORE Combats Glioblastoma

- Improving Immune Response Against Viral Infections and Disease

- Revising Theory of Cancer-Induced Immune Suppression

- Some Chemotherapy Side Effects Could Be Prevented

- Surface Protein Helps Tumor Cells Form Clusters

- Transcription Elongation Checkpoint Discovered

- Resident Unionization Doesn’t Impact Burnout

- Uncovering Epigenetic Mechanisms Regulating Glioma Growth

- Strengthened Microtubules Aid Cell Migration

- Gene Implicated in Poor Skin Cancer Therapy Outcomes

- Using Circulating Tumor DNA to Target Immunotherapy

- Nanoparticles Could Boost Immunotherapy

- Combined Therapy Shows Promise for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

- Novel Therapy May Improve Survival for Malignant Gliomas

- Virtual Intervention Reduces Fear of Breast Cancer Recurrence

- Novel Treatments to Prevent Infections in Patients with Leukemia

-

News

>

- Northwestern Medicine at the 2024 ASCO® Annual Meeting

- 2023 Year in Review | Northwestern Medicine Lurie Cancer Center Year

- Lurie Cancer Center Investigators Recognized on 2023 'Highly Cited' List

- Cella Named 2023 Tripartite Prize Recipient

- Brain Tumor SPORE Receives $10.8 Million NCI Award Renewal

- Chandel Receives 2023 Lurie Prize in Biomedical Sciences

- Mario Shields Receives NCI Cancer Moonshot Scholars Award

- Dr. June McKoy Named to NCCN Forum on Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Global Health Day Highlights Education, Research and Outreach

- CME: Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma with Adam Sonabend, MD

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

-

Ophthalmology

>

-

Clinical Breakthroughs

>

- Case Report: Intraocular Foreign Body

- Case Study: Staircase Lamellar Macular Hole

- Case Report: Eye Muscle Surgery for Severe Exotropia

- Proton Beam Therapy for Complex Choroidal Melanoma

- Advancing LGBTQ+ Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in Ophthalmology

- Insights on Ocular Syphilis From Debra A. Goldstein, MD

- Ophthalmology Sustainability Practices and Future Directions for Sustainability at Northwestern Medicine

- Layers of Ocular Oncology

- AI-Driven Diabetic Retinopathy Screening

- Drug Waste and How Physicians Can Move the Needle

- Case Report: Extranodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma of the Ocular Adnexa

- Case Report: Orbital Necrotizing Fasciitis Due to Severe Odontogenic Infection

- Complex Ophthalmology Cases: A Discussion With Neuro-Ophthalmology and Oculoplastics

- Preventive Anti-VEGF Therapy Does Not Improve Outcomes for Patients with NPDR

- Case Report: Bilateral Disc Edema in an Overweight Female Patient

- Sustainable Ophthalmology: Waste Management in the OR

- Proton Beam Therapy and Plaque Brachytherapy for Uveal Melanoma

- A Case of Downbeat Nystagmus and Oscillopsia

- Reducing Health Disparities in Glaucoma Treatment

- Case Report: Pulsatile Proptosis Due To Orbitocranial Trauma

- Cataract Surgery in Uveitis Patients

- Oculoplastics: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Complex Cases

- How to Avoid Neuro-ophthalmic Catastrophes: Safe, Not Sorry

- Inside the OR | Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Cataract Surgery

- Case Report: Surgical Management of Negative Dysphotopsia

- Treatments for Advanced Diabetic Retinopathy Show Similar Results

- Collaborations and Controversies: Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS)

- Collaborations and Controversies: Femtosecond Laser Cataract Surgery

- Rho Kinase Inhibitors as a Novel Treatment for Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension

- Exploring Refractive Cataract Surgery

- Updates in Care for Diabetic Retinopathy

- Building a Foundation for Treatment of Complex Ophthalmic Conditions

- Lid Abscess Associated With Personal Protective Eyewear in COVID-19 Unit

-

Research

>

- Genetic Mechanisms May Reveal Retinal Vascular Disease Therapeutic Targets

- Proteomimetic Polymers Show Anti-angiogenic Activity in AMD Mouse Model